LIFE MAGAZINE

LIFE was an American magazine that ran weekly from 1883 to 1972, published initially as a humor and general interest magazine. Time founder Henry Luce bought the magazine in 1936, solely so that he could acquire the rights to its name, and shifted it to a role as a weekly news magazine with a strong emphasis on photojournalism. LIFE was published weekly until 1972, as an intermittent “special” until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 to 2002.

When LIFE was founded in 1883, it was developed as similar to the British magazine, Puck. It was published for 53 years as a general-interest light entertainment magazine, heavy on illustrations, jokes and social commentary. It featured some of the greatest writers, editors, illustrators and cartoonists of its era, including Charles Dana Gibson, Norman Rockwell and Jacob Hartman Jr. Gibson became the editor and owner of the magazine after John Ames Mitchell died in 1918. During its later years, the magazine offered brief capsule reviews (similar to those in The New Yorker) of plays and movies currently running in New York City, but with the innovative touch of a colored typographic bullet resembling a traffic light, appended to each review: green for a positive review, red for a negative one, and amber for mixed notices.

The Luce version of LIFE was the first all-photographic American news magazine, and it dominated the market for more than 40 years. The magazine sold more than 13.5 million copies a week at one point; it was so popular that President Harry S. Truman, Sir Winston Churchill, and General Douglas MacArthur all had their memoirs serialized in its pages.

Perhaps one of the best-known pictures printed in the magazine was Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photograph of a nurse in a sailor’s arms, snapped on August 27, 1945, as they celebrated VJ Day in New York City. The magazine’s role in the history of photojournalism is considered its most important contribution to publishing. LIFE was wildly successful for two generations before its prestige was diminished by economics and changing tastes.

LIFE’s online presence began in the 1990s as part of the Pathfinder.com network. The standalone Life.com site was launched March 31, 2009 and closed January 30, 2012.

LIFE was founded January 4, 1883, in a New York City artist’s studio at 1155 Broadway, as a partnership between John Ames Mitchell and Andrew Miller. Both men retained their holdings until their deaths. Miller served as secretary-treasurer of the magazine and was very successful managing the business side of the operation. Mitchell, a 37-year-old illustrator who used a $10,000 inheritance to invest in the weekly magazine, served as its publisher. Mitchell created the first LIFE name-plate with cupids as mascots; he later drew its masthead of a knight leveling his lance at the posterior of a fleeing devil. Mitchell took advantage of a revolutionary new printing process using zinc-coated plates, which improved the reproduction of his illustrations and artwork. This edge helped because LIFE faced stiff competition from the best-selling humor magazines Judge and Puck, which were already established and successful. Edward Sandford Martin was brought on as LIFE’s first literary editor; the recent Harvard graduate was a founder of the Harvard Lampoon.

The motto of the first issue of LIFE was: “While there’s Life, there’s hope.” The new magazine set forth its principles and policies to its readers:

“We wish to have some fun in this paper… We shall try to domesticate as much as possible of the casual cheerfulness that is drifting about in an unfriendly world… We shall have something to say about religion, about politics, fashion, society, literature, the stage, the stock exchange, and the police station, and we will speak out what is in our mind as fairly, as truthfully, and as decently as we know how.”

The magazine was a success and soon attracted the industry’s leading contributors. Among the most important was Charles Dana Gibson. Three years after the magazine was founded, the Massachusetts native first sold LIFE a drawing for $4: a dog outside his kennel howling at the moon. Encouraged by a publisher who was also an artist, Gibson was joined in LIFE’s early days by such well-known illustrators as Palmer Cox (creator of the Brownie), A.B. Frost, Oliver Herford, and E.W. Kemble. LIFE attracted an impressive literary roster too: John Kendrick Bangs, James Whitcomb Riley and Brander Matthews all wrote for the magazine around the start of the 20th century.

LIFE became a place that discovered new talent; this was particularly true among illustrators. In 1908 Robert Ripley published his first cartoon in LIFE, 20 years before his Believe It or Not! fame. Norman Rockwell’s first cover for Life, Tain’t You. was published May 10, 1917. Rockwell’s paintings were featured on Life‘s cover 28 times between 1917 and 1924. Rea Irvin, the first art director of The New Yorker and creator of the character “Eustace Tilley”, got his start drawing covers for Life.

Charles Dana Gibson dreamed up the magazine’s most celebrated figure in its early decades. His creation, the Gibson Girl, was a tall, regal beauty. After appearances in LIFE in the 1890s, the image of the elegant Gibson Girl became the nation’s feminine ideal. The Gibson Girl was a publishing sensation and earned a place in fashion history.

This version of LIFE took sides in politics and international affairs, and published fiery pro-American editorials. Mitchell and Gibson were incensed when Germany attacked Belgium; in 1914 they undertook a campaign to push the United States into the war. Mitchell’s seven years studying at Paris art schools made him partial to the French; there was no unbiased coverage of the war. Gibson drew the Kaiser as a bloody madman, insulting Uncle Sam, sneering at crippled soldiers, and shooting Red Cross nurses. Mitchell lived just long enough to see LIFE’s crusade result in the U. S. declaration of war in 1917.

Following Mitchell’s death in 1918, Gibson bought the magazine for $1 million, but the world had changed. It was not the Gay Nineties, when family-style humor prevailed and the chaste Gibson Girls wore floor-length dresses. World War I had spurred changing tastes among the magazine-reading public. LIFE’s brand of fun, clean and cultivated humor began to pale before the new variety: crude, sexy and cynical. LIFE struggled to compete on newstands with such risqué rivals. A little more than three years after purchasing LIFE, Gibson quit and turned the decaying property over to publisher Clair Maxwell and treasurer Henry Richter. Gibson retired to Maine to paint and lost active interest in the magazine, which he left deeply in the red.

LIFE had 250,000 readers in 1920, but as the Jazz Age rolled into the Great Depression, the magazine lost money and subscribers. By the time Maxwell and Editor George Eggleston took over, LIFE had switched from publishing weekly to monthly. The two men went to work revamping its editorial style to meet the times, and in the process it did win new readers. Despite all-star talents on staff, LIFE had passed its prime and was sliding toward financial ruin. The New Yorker, debuting in February 1925, copied many of the features and styles of LIFE; it recruited staff from its editorial and art departments. LIFE struggled to make a profit in the 1930s when Henry Luce pursued purchasing it.

In 1936 publisher Henry Luce paid $92,000 to the owners of LIFE magazine because he sought the name for his company, Time, Inc. Convinced that pictures could tell a story instead of just illustrating text, Luce launched LIFE on November 23, 1936. LIFE developed as the premiere photo magazine in the U.S., giving as much space and importance to images as to words. The first issue of LIFE, which sold for ten cents, (worth $2 today) featured five pages of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photographs.

The format of LIFE in 1936 was an instant classic: the text was condensed into captions for 50 pages of photographs. The magazine was printed on heavily coated paper and cost readers only a dime. The magazine’s circulation sky-rocketed beyond the company’s predictions, going from 380,000 copies of the first issue to more than one million a week four months later.

When the U. S. entered the war in 1941, so did LIFE. By 1944, of the 40 Time and LIFE war correspondents, seven were women. LIFE was pro-American and backed the war effort each week. In July 1942, LIFE launched its first art contest for soldiers and drew more than 1,500 entries, submitted by all ranks. Judges sorted out the best and awarded $1,000 in prizes. LIFE picked 16 for reproduction in the magazine. The National Gallery in Washington, DC agreed to put 117 entries on exhibition that summer. LIFE, in its patriotism, also supported the military’s efforts to use artists to document the war. When Congress forbade the armed forces from using government money to fund artists in the field, LIFE privatized the programs, hiring many of the artists being let go by the Department of Defense (DOD).

Each week during World War II, the magazine brought the war home to Americans; it had photographers in all theaters of war, from the Pacific to Europe. The magazine was so iconic that it was imitated in enemy propaganda using contrasting images of Life and Death.

LIFE in the 1950s earned a measure of respect by commissioning work from top authors. After LIFE’s publication in 1952 of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, the magazine contracted with the author for a 4,000-word piece on bullfighting. Hemingway sent the editors a 10,000-word article, following his last visit to Spain in 1959 to cover a series of contests between two top matadors. The article was republished in 1985 as the novella, The Dangerous Summer.

In February 1953, just a few weeks after leaving office, President Harry S. Truman announced that LIFE magazine would handle all rights to his memoirs. Truman said it was his belief that by 1954 he would be able to speak more fully on subjects pertaining to the role his administration played in world affairs. Truman observed that LIFE editors had presented other memoirs with great dignity; he added that LIFE also made the best offer.

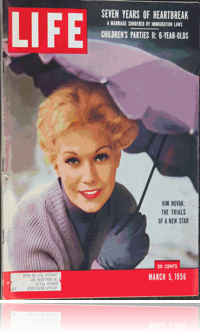

In November 1954, the actress Dorothy Dandridge was the first African-American woman to be featured on the cover of the magazine.

LIFE’s motto became, “To see Life; to see the world.” In the post-war years it published some of the most memorable images of events in the United States and the world. The magazine continued to showcase the work of notable illustrators, such as Alton S. Tobey, whose many contributions included the cover for a 1958 series of articles on the history of the Russian Revolution.

But, as the 1950s drew to a close and TV became more popular, the magazine was losing readers. In May 1959 it announced plans to reduce its regular news-stand price to 19 cents a copy from 25 cents. With the increase in television sales and viewership, interest in news magazines was waning. LIFE had to try to create a new form.

In the 1960s the magazine was filled with color photos of movie stars, President John F. Kennedy and his family, the war in Vietnam, and the Apollo program. Typical of the magazine’s editorial focus was a long 1964 feature on actress Elizabeth Taylor and her relationship to actor Richard Burton.

In the 1960s, the magazine’s photographs featured those by Gordon Parks. “The camera is my weapon against the things I dislike about the universe and how I show the beautiful things about the universe,” Parks recalled in 2000. “I didn’t care about Life magazine. I cared about the people,” he said.

On March 25, 1966, LIFE featured the drug LSD as its cover story; it had attracted attention among the counter culture and was not yet criminalized.

In March 1967, LIFE won the 1967 National Magazine Award, chosen by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The prestigious award was made for the magazine’s publication of stunning photos from the war in Southeast Asia, such as Henri Huet’s riveting series of a wounded medic that were published in January 1966. Increasingly, the photos that LIFE published of the war in Vietnam were searing images of death and loss.

But, despite the industry’s accolades and publishing America’s mission to the moon in 1969, the magazine continued to lose circulation. LIFE was reportedly not losing money, but its costs were rising faster than its profits. LIFE lost credibility with many readers when it supported author Clifford Irving, whose fraudulent autobiography of Howard Hughes was revealed as a hoax in January 1972. The magazine had purchased serialization rights to Irving’s manuscript.

From 1972 to 1978, Time Inc. published ten Life Special Reports on such themes as “The Spirit of Israel”, “Remarkable American Women” and “The Year in Pictures”. With a minimum of promotion, those issues sold between 500,000 and 1 million copies at cover prices of up to $2.

LIFE continued for the next 22 years as a moderately successful general-interest, news features magazine. In 1986, it decided to mark its 50th anniversary under the Time Inc. umbrella with a special issue showing every LIFE cover starting from 1936, which included the issues published during the six-year hiatus in the 1970s. The circulation in this era hovered around the 1.5 million-circulation mark. The cover price in 1986 was $2.50.

The magazine struggled financially and, in February 1993, LIFE announced the magazine would be printed on smaller pages starting with its July issue. This issue also featured the return of the original LIFE logo.

The magazine was back in the national consciousness upon the death in August 1995 of Alfred Eisenstaedt, the LIFE photographer whose photographs constitute some of the most enduring images of the 20th century. Eisenstaedt’s photographs of the famous and infamous – Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, Marilyn Monroe, Ernest Hemingway, the Kennedys, Sophia Loren – won him worldwide renown and 86 LIFE covers.

In 1999 the magazine was suffering financially, but still made news by compiling lists to round out the 20th Century. LIFE editors ranked its “Most Important Events of the Millennium.” LIFE also published a list of the “100 Most Important People of the Millennium.”

In March 2000, Time Inc. announced it would cease regular publication of LIFE with the May issue, seven months before the century’s end.

The magazine’s last issue featured a human interest story. In 1936 its first issue under Henry Luce featured a baby named George Story, with the headline “Life Begins”; over the years the magazine had published updates about the course of Story’s life as he married, had children, and pursued a career as a journalist. After Time announced its pending closure in March, George Story happened to die of heart failure on April 4, 2000.

While citing poor advertising sales and a rough climate for selling magazine subscriptions, Time Inc. executives said a key reason for closing the title in 2000 was to divert resources to the company’s other magazine launches that year. Later that year, its parent company, Time Warner, struck a deal with the Tribune Company for Times Mirror magazines, which included Golf, Ski, Skiing, Field & Stream, and Yachting. AOL and Time Warner announced a $184 billion merger, the largest corporate merger in history, which was finalized in January 2001.

In 2001 Time Warner began publishing special newsstand “megazine” issues of LIFE, on topics such as the 9/11 attacks and the Holy Land. These issues, which were printed on thicker paper, were more like softcover books than magazines.

Beginning in October 2004, LIFE was revived for a second time. It resumed weekly publication as a free supplement to U.S. newspapers, competing for the first time with the two industry heavyweights, Parade and USA Weekend. At its launch, it was distributed with more than 60 newspapers with a combined circulation of approximately 12 million. Time Inc. made deals with several major newspaper publishers to carry the LIFE supplement, including Knight Ridder and The McClatchy Company.

This version of LIFE retained its trademark logo but sported a new cover motto, “America’s Weekend Magazine.” It measured 9½ x 11½ inches and was printed on glossy paper in full-color. On September 15, 2006, LIFE was 19 pages. This era of LIFE lasted less than three years. On March 24, 2007, Time Inc. announced that it would fold the magazine as of April 20, 2007, although it would keep the web site.

On November 18, 2008, Google began hosting an archive of the magazine’s photographs, as part of a joint effort with LIFE. Many images in this archive had never been published in the magazine. The archive of over 6 million photographs from Life is also available through Google Cultural Institute.

The standalone Life.com site was launched March 31, 2009 and closed January 30, 2012. Life.com was developed by Andrew Blau and Bill Shapiro, the same team who launched the weekly newspaper supplement. While the archive of LIFE, known as the LIFE Picture Collection, was substantial, they searched for a partner who could provide significant contemporary photography. They approached Getty Images, the world’s largest licensor of photography. The site, a joint venture between Getty Images and LIFE magazine, offered millions of photographs from their combined collections.

The film, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, starring Ben Stiller and Kristen Wiig, portrays LIFE as it transitioned from printed material toward having only an online presence. Life.com is now a redirect to a small photo channel on Time.com.