Coca-Cola Advertisements in World War II

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941 Coca-Cola was already bottled and sold throughout the country. In order show support for the brave men and women and an astute marketing plan Coca-Cola President Robert Woodruff declared that “every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents, wherever he is and whatever it costs the company”. Five cents was the cost of a bottle of Coca-Cola in the Untied States.

In 1943 General Dwight D. Eisenhower commander of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations for all allied forces requested 3 million bottles of Coca-Cola to be shipped to North Africa. He also asked for equipment to construct ten bottling plants. After the bottling plants were constructed the Coca-Cola Company sent 148 of its employees oversees to maintain and manage the plants. The employees were given US Army uniforms, the rank of Technical Observer and treated as officers. They were nicknamed the “Coca-Cola Colonels” by the soldiers.

From the 1940s through 1960 the number of countries with bottling plants nearly doubled. While the Coca-Cola Company was busy boosting the morale of the fighting forces, they were also laying the foundation for becoming an international symbol of refreshment. Most of the bottling plants constructed overseas continued to operate when the war ended.

Coca-Cola’s advertisements during the war focused on coming together and enjoying the little things in life and avoided imagery of conflict. The taglines used would sound familiar to us today. “…Have a Coke”, “The pause that refreshes”, “That Extra Something!”, and “The Real Thing…”.

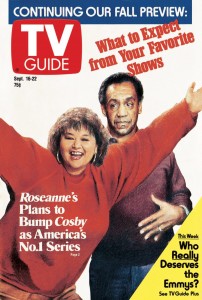

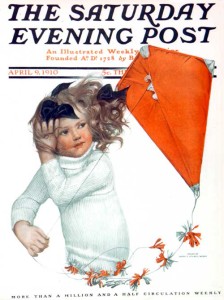

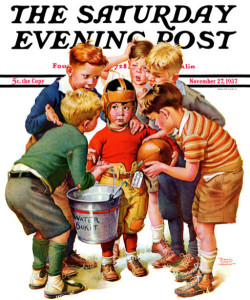

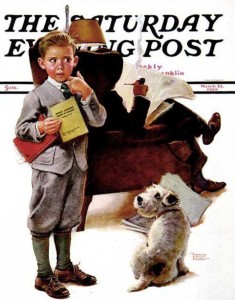

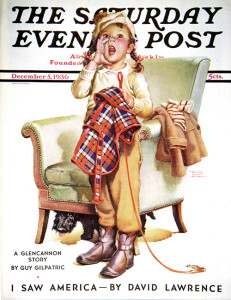

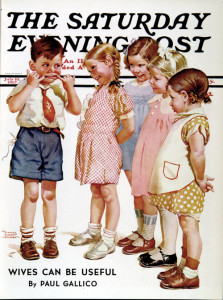

Below are nine advertisements for Coca-Cola from the back of Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post from 1942 to 1946. The style of the illustration are familiar to us today with rosy faced people smiling, coming together to enjoy life and drink coke. Something to notice is that most of the service personal pictured are not officers but privates and corporals or no rank is shown, Coca-Cola is the drink for everyone.

To leave comment or suggestions please click the pencil icon to the right of the post.

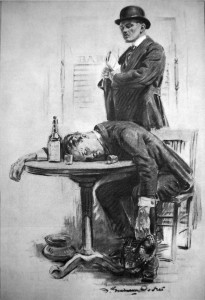

Collier’s. August 01, 1942

This advertisement assures the public that the war rationing has not changed the quality of the product with the tagline “Coca-Cola, you know it’s the real thing” and an unnamed mascot with a bottle cap hat proclaiming “I’m loyal to quality”.

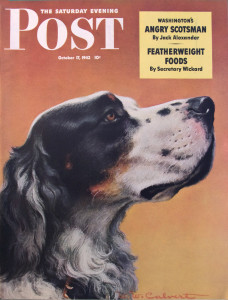

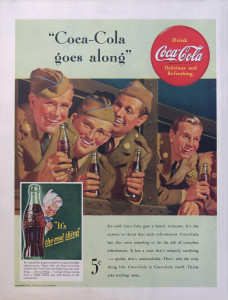

The Saturday Evening Post. October 17, 1942

This advertisement also assures the public that the war rationing has not changed the quality of the product “It’s the real thing” and Coca-Cola is going to war with the troops, “Coca-Cola goes along” a sort of we are all in this together.

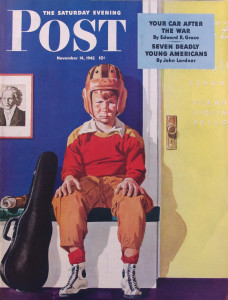

The Saturday Evening Post. November 14, 1942

This advertisement focuses on the home front and still assures the public that the quality has not changed thought it may be hard to find. The ad mentions Coca-Cola is the pause that refreshes and part of the simple pleasures in life with the tagline “That Extra Something!…You can spot it every time”.

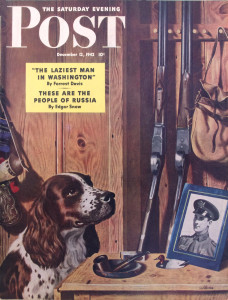

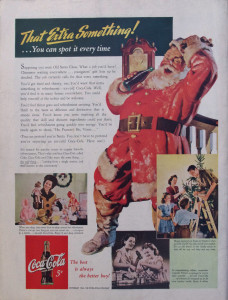

The Saturday Evening Post. December 12, 1942

This advertisement focuses on refreshment and the energy that you will need while shopping or if Santa delivering presents all night. Coca-Cola did not create the image of jolly old Santa but they did solidify our modern image of him in a red suit and pure white beard.

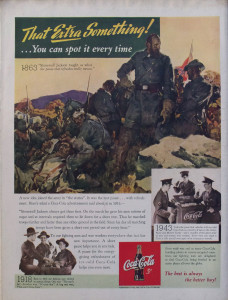

The Saturday Evening Post. May 01, 1943

This advertisement features “…the pause that refreshes” by mentioning how a rest pause in the military helps with any task and gives three examples. Stonewall Jackson in 1863 (without Coca-Cola), 1918 World War I and 1943 World War II.

The Saturday Evening Post. August 21, 1943

This advertisement focuses on our troops overseas and that Coca-Cola is there as a familiar friend. A little piece of home that can be enjoyed all over the globe.

The Saturday Evening Post. December 09, 1944

Another Christmas advertisement, this one emphases friends and family and how Coca-Cola is an everyday symbol of hospitality. A way to be friendly all over the globe is to offer people “Have a Coke…”. Strangely for a portrait of a family there are no adult woman in the illustration.

The Saturday Evening Post. December 08, 1945

Christmas 1945 the war is over and the troops are arriving home. All the dreams of a soldier coming home include wife, children and Coca-Cola and that it is now the way to be hospitable around the world.

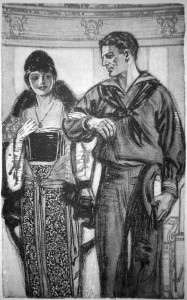

The Saturday Evening Post. February 02, 1946

In this advertisement the troops are heading home with their overseas stripes on their sleeves and a Coca-Cola in their hands. They enjoyed the soft drink overseas brightening many a drab moment and now that they are home a bottle of Coke is a way to continue the tradition.